Looking at the full scope of PAD: Cases, techniques, and economic considerations for complex disease.

A Physician Perspective on Collaborating With Your Hospital’s Value Analysis Committee

Speaking with a physician leader at Atrium Health’s Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute about advocating for physician device preferences and effectively communicating with key stakeholders.

WITH FRANK R. ARKO III, MD

How has your organization changed in regard to decision-making as we move into the age of value-based care?

We are slowly moving into different reimbursement models for physicians, looking at quality outcomes as part of our way of paying them. Part of our pay structure involves value-based metrics. We look at our readmission rate on a yearly basis, and we try to put methods into place that will decrease that readmission rate. We also look at patient satisfaction with both our system and our physicians. Looking at these data, we are not afraid to make changes to make it fair for everyone involved.

Additionally, we have started to not just look at technologies at the time of implant; we also consider their indication and the potential long-term results. This helps us improve the quality of the procedure and long-term outcomes in order to decrease readmissions and secondary admissions.

What role do physicians play in value analysis?

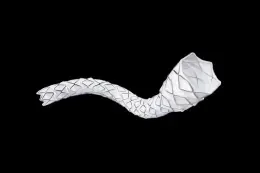

The value analysis committee works as a physicianadministration dyad. From that team standpoint, we consider all available products. Within a 2-, 3-, or 4-year period, we’ll go through a request for proposal (RFP) process with the varying manufacturers. As we sort through the data, we look at the quality of the data and the indication each device has for therapy and weigh out which devices need to be stocked. For instance, the RFP from one company that covers a broad range of devices may not include a stent that has indication for the popliteal artery, because they do not make one. In that case, we would include a device from another company that does have a popliteal artery stent. This goes to the quality of patient care; we want to do what is right for the patient, and if we have information that says a stent has been studied for a particular indication we need, then we need to keep that stent.

Physicians need to be the advocates in situations like this because they are the most knowledgeable about disease processes and device indication. You need a physician who wants to be readily involved in that process. Oftentimes that is a nonpaying position, but it wields a lot of power and information that will allow you access to the devices and implants you need. If you abdicate full control of device selection to administrators, at some point, you will be told what you can and cannot use to treat your patients and lose the ability to care for them in the way you believe is best.

What information does the committee usually expect from physicians?

The committee will ask physicians if one device is superior. When talking about plain old balloon angioplasty, as opposed to an antiproliferative or a stent, they will ask if one balloon is better than the others. At this point, there is not a significant difference in those types of commodities, so their selection is generally dictated by cost.

However, physician involvement becomes more important when you look at long-term implants. An administrator may not consider certain factors, like the risk of stent fractures. For instance, a company will offer a first- or second-generation product with known failures for half the price than other companies. The administrators may not know or understand the complete picture on that device. Does it have a high risk of target lesion revascularization or fractures? Does the device have a limited indication for a certain arterial bed? The committee may not understand how a device works, what is considered on- and off-label use, or how to interpret performance rates over time. It is important for physicians to speak up and use the available published data and experiential knowledge they have to make a strong argument as to why the hospital needs to go with a device that is more expensive but adds value in the form of lower associated rates of readmission or better-quality care. The device may have some incremental price increases, but if it causes no adverse events, the hospital is increasing value. These details are the physicians’ responsibility to advocate, and it is important to develop a relationship with those administrators so that they can understand it.

What are the best approaches for a successful collaboration between physicians and the committee?

Administrators need to be open to increasing their knowledge of the clinical consequences of certain devices and tools. Fortunately, our institution’s administrators are good at working with physicians because they know they don’t have that clinical knowledge. That may not necessarily be true at every institution. Physicians need to look at the clinical data and information, but then also be able to put on a business management hat. Different devices come out and physicians want to utilize them because they are new and unique, but they may not necessarily offer any value or outcome improvement. We need to be honest about that and not bring in every new device. The industry also plays a role. They must understand that they need to bring the data and information that will help the committee make the best choices for all parties involved.

How do you manage diversity of opinion among physicians about which devices to bring in?

I want every physician to feel that they can treat patients the way they want to. You can’t say that someone with a certain disease must be treated one particular way every time. In doing so, approximately 20% of patients will receive the wrong therapy. Physicians need to work as a team and ask what the best management is for a disease process.

How do you assess the differences between higher- and lower-cost items and procedures?

Ideally, the cost per procedure per physician should be a bell curve; most physicians are at the top of the bell curve, with some who are cheaper and some who are more expensive. An administrator might look at that and ask for everyone to shift to the methods of the lower-cost individual. However, the committee needs to evaluate why the difference occurs. A physician at the higher end of the curve may have more complex cases, and a physician at the lower end of the curve may have simpler cases. The more expensive physician could be overusing devices and implants, or that physician could be the world expert in a specific procedure that demands higher costs.

With the administration, we ask what we can do to lower the cost of more expensive procedures. Renegotiation of device price with the manufacturer is one step, but at times we cannot, so there are other ways to reduce cost and improve diagnosis-related group reimbursement.

For example, we lowered our cost for endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) first by getting the device price to something very reasonable. Asking what else we could do to decrease costs, we started performing EVAR percutaneously with almost all patients. With this method, we can treat the patient and discharge them the next day. We had better results than if the patient stayed for 2 days, and they had less pain when treated percutaneously. The next step was to look at the other EVAR procedural costs. If every patient is asleep in the operating room, then we need an anesthesiologist, an arterial line, and a Foley catheter. Our new method shifts very straightforward patients out of the operating room and into the catheterization laboratory, which saves nearly $5,000 per case. There are a multitude of ways to consider cost, but it is important to have physicians and administration working together to give the best value to the patient.

When it comes to product selection, how is it determined if a new product is essential to the quality of care for your patients?

First, we need a physician champion for the product. Then we evaluate the product with a short trial period, asking if this is something we want to utilize, how it worked in previous cases, and if it performed significantly better than other devices. If the trial period is successful, it goes to the value analysis committee. It can be helpful to speak to individuals on that value analysis committee beforehand, so you can develop some champions on the committee. It’s important to come to the committee with an understanding of how the product will improve quality and outcomes based on the data. We ask if it is a novel device; if it is, will it increase costs but replace the need for other products? That is the algorithm that we look at to bring in a new product.

If a manufacturer has a new product available in a lower French size, it’s unreasonable to charge twice the amount of money for an incremental improvement in the device. If that is the case, we will probably keep what we have already, unless the manufacturer wants to replace the old device and charge the same price.

However, if a device costs more but the data suggest a marked improvement, it is not as simple. Physicians must explicitly explain to the administration how the data are significantly better and will benefit patients. Utilizing that data, the goal is to reach a compromise between administration, physicians, and industry to bring in the best device for the patient at a reasonable price.

RESEARCHING ANY DATA, REGISTRIES, AND TRIALS IS HELPFUL. DATA ON DECREASING MORTALITY, INTERVENTIONS, AND COMPLICATIONS ON THE PROCEDURES WILL ALSO AID US IN MAKING OUR ARGUMENT.

What resources are used and who is responsible for gathering and interpreting product selection information? How does your hospital score that kind of information?

There is not a scoring system, per se, but it is related to how well the physician can make the argument to the administration. The physician and the device manufacturer are responsible for gathering the information. Researching any data, registries, and trials is helpful. Data on decreasing mortality, interventions, and complications on the procedures will also aid us in making our argument. When going to the committee, I would suggest that physicians have all this research summarized, so they can look at and present the big bullet points. Any physician can initiate bringing in a product for the trial period, but it is helpful to have someone at that top level to team up with.

What advice would you give physicians and hospital administration for navigating the value analysis process?

Physicians, especially young physicians, should understand product cost. The more vested interest they have in the quality and value of a procedure, the more they will understand the need to evaluate whether a product offers value and improved outcomes for a patient or if it is just another tool in the toolbox. The business side of medicine should be instituted earlier in a physician’s training because there’s often a void when it comes to financial implications. The amount the United States spends on health care is increasing, and physicians need to become knowledgeable about this. The only way to solve the problem is to have physicians directly involved.

Physicians should build a relationship with administration by continuously trying to reduce procedure costs. The stronger the working relationship is with the physician and the administration, the easier it will be to bring in a device they believe in. Transparency between physicians and administration is also important. An institution can tell how costly each physician is for a specific procedure. Sharing those data with physicians is helpful because they can see where they are on the bell curve. No one wants to be the outlier, but if they do not know they are the outlier, it is hard to change. This transparency can improve the quality of care for patients.

Institutions do not share these data as often as they should. My institution tries to develop a team approach to managing and caring for a patient, so the administrators share that information with the physicians. I think this team approach between physicians and administration is a fantastic way to develop better health care to deliver to patients, both from a clinical and an economic standpoint, as it allows both sides of the institution to utilize their respective expertise. Similarly, an engineer developing a medical device doesn’t necessarily understand all the clinical implications, and a physician developing a device doesn’t necessarily understand all the engineering components involved. Together, however, they can create a product that is markedly better than anything created by either one on their own. I think the same is true for the deliverance of health care with physicians and hospital administration.

How do you think value-based care will evolve in the next 5 to 10 years?

It’s evolving daily, so it is hard to say, but I am supportive of it and believe there will be more of it. I also think physicians need to be involved in institutional decision-making to make sure that value-based care is implemented in the best possible way for maintaining the care of the patient. Physicians must be vocal advocates for their patients.

Frank R. Arko III, MD

Chief, Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Professor, Cardiovascular Surgery

Co-Director, Aortic Institute

Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute

Atrium Health

Charlotte, North Carolina

Disclosures: Consultant to Gore & Associates, Medtronic, Penumbra, Philips, and Cook Medical; does research for Gore & Associates, Medtronic, Penumbra, Silk Road, and Cook Medical.